| Title: | On the Hebrew vowel HOLAM |

| Source: | Peter Kirk |

| Status: | Individual Contribution |

| Action: | For consideration by the UTC |

| Date: | 2004-06-05 |

The proposer gratefully

acknowledges the help of Jony Rosenne in preparing this proposal.

The Hebrew point HOLAM combines in two different

ways with the Hebrew letter VAV. In

the first combination, known as Holam Male,

the VAV is not pronounced as a consonant, and HOLAM

and VAV together serve as the vowel associated with the

preceding consonant. In the second combination, known as Vav Haluma,

the HOLAM is the vowel of a

consonantal VAV. In

high quality typography Holam Male

is distinguished from Vav Haluma: Holam Male is written

with the HOLAM dot above the right side

or above the centre of VAV;

and Vav Haluma

is written with HOLAM above the top left

of VAV. The distinction is clear and significant in

some texts, dating from the 10th century CE to the present day. But in

less high quality typography Holam

Male and Vav Haluma

are not distinguished,

and usually both rendered with the HOLAM dot above the

centre of VAV. Holam

Male

is very common in pointed Hebrew texts; Vav Haluma is much less common but

not

extremely rare.

Note carefully that this is not

a proposal to encode a phonetic

distinction which is not made graphically. Rather, it is a proposal to

encode a graphical

distinction with a 1000 year history. This graphical distinction is

often, although not always, made in modern texts, and it must be made

when the phonetic distinction needs to be indicated unambiguously.

Unicode does not currently specify how to distinguish between Holam Male, Vav Haluma, and the undifferentiated combination. Several different ways have been used in existing texts, or recommended for use with Unicode Hebrew fonts. To avoid proliferation of ad hoc solutions, it is proposed here that the UTC specify encodings for the three cases.

Several options are outlined below. The

preferred option is to encode Holam

Male, when

distinguished from Vav Haluma,

as

the sequence <VAV,

ZWJ, HOLAM>. This option is proposed

to the UTC.

There are two ways of indicating vowels in Hebrew script, which may

be

used either separately or in combination. The ancient system, which

does not fully distinguish the vowel sounds, is to insert the Hebrew

letters ALEF, HE,

VAV and YOD, which can therefore

function as vowels as well as consonants. When "silent", i.e. used to

indicate vowels,

these letters are known mothers of

reading (imot qeri'a or

ehevi in Hebrew, matres lectionis in Latin). In the

early mediaeval period several different systems of pointing were

introduced to specify the vowel sounds more precisely. Only one of

these systems, the Tiberian system, is in current use, and this is the

only one currently encoded in Unicode. (Proposals for the other systems

are currently being prepared.) This system is normally used for

the biblical and other ancient texts (although not for synagogue

scrolls, which are unpointed) and for some modern Hebrew texts. Most

modern Hebrew is unpointed, but makes good use of mothers of reading.

One of the Tiberian vowel points, U+05B9 HEBREW POINT HOLAM,

consists of a dot

usually

written above the left side of a Hebrew base character. This

represents a long O sound pronounced after the base character. When

there is no associated mother of

reading, this way

of writing a long O sound is known as Holam

Haser, i.e. Defective Holam.

In old manuscripts, the dot is often positioned over the space

between the preceding and following base characters, and sometimes

above the right side of the following (to the left) base character. In

printed texts,

the regular position of the dot is above the left side of the preceding

base character.

In pointed Hebrew text the same vowel is often represented both by a

vowel point and by a mother of

reading. The latter has no vowel point of its own, because the

vowel is associated with the preceding consonant. The commonest mother of

reading for a long O sound is VAV. Therefore the

combination of HOLAM with a VAV mother of reading is common in

pointed texts. This

combination is known as Holam Male

(Male is pronounced as two

syllables, mah-leh), i.e. Full Holam.

The HOLAM dot is logically associated with the

preceding base character, the consonant for which it indicates the

vowel sound; the VAV

is redundant because the vowel is fully indicated by the HOLAM.

Thus the VAV may be considered silent, corresponding to

the general rule for pointed texts that a non-final base character with

no point is silent; an alternative analysis is that the VAV

and the HOLAM together indicate the vowel sound.

In the oldest manuscripts which use this pointing scheme, dating from

the 10th century CE, the dot

was positioned above the space between the preceding base character and

the VAV, but it has gradually shifted on to the

redundant VAV.

In modern high quality typography the dot is positioned above the VAV,

usually above its right edge or its centre. However, the HOLAM

dot is not shifted on to a following VAV when the VAV

is not silent but consonantal, except sometimes in rendering the divine

name.

The difficulty arises because VAV can also be a consonant, and as such can be followed, like every other consonant, by Holam Haser (or by Holam Male, but this causes no special difficulty). Therefore the HOLAM dot can combine in two logically different ways with VAV. The combination of VAV with Holam Haser is known as Vav Haluma, and is pronounced VO (or in some traditions WO). A combination of VAV with HOLAM could be a Holam Male, where the VAV is silent and the letter VAV and the point HOLAM together represent the vowel; or it could be the letter VAV with a Holam Haser, where the VAV is a consonant and the HOLAM point is a vowel. There is no difference in pronunciation between Holam Male and Holam Haser.

In high quality typography, especially of the Hebrew Bible and other religious texts, of educational materials, and of poetry, a careful distinction is made between Holam Male and Vav Haluma: in Holam Male, the HOLAM dot is positioned above the right side of the VAV, or sometimes centred above the VAV; but in Vav Haluma, Holam Haser is rendered in its normal position above the left side of VAV. This seems to have been the original practice, as witnessed in manuscripts and printed editions from the 10th to 19th centuries CE. But, because VAV is a rather narrow letter, and because Vav Haluma is rare in modern Hebrew (in which long O is usually written as Holam Male), many modern typographers of general texts make no distinction, rendering both Holam Male and Vav Haluma by VAV with a HOLAM dot usually centred above it.

The distinction between Holam Male

and Vav Haluma is an

important and

semantically significant one. This is especially true for religious

texts; the

distinction is made in most Hebrew Bible editions, and in texts quoting

from the Bible. It is also important in educational materials and in

poetry, wherever the exact pronunciation must be marked unambiguously.

See the

examples in Figures 1, 2 and 3 below, in which Holam Male and Vav Haluma are distinguished in six

Hebrew Bible editions and in two other works.

This distinction is not a rare one. Holam Male is very common in the

Hebrew Bible, occurring about 34,808 times or in about 13% of all

words. Vav Haluma is much

less

common, occurring about 421 times.

|

|

|

| Codex Leningradensis (1006-7) | Lisbon Bible (1492) | Rabbinic Bible (1524-5) |

|

|

|

| Ginsburg/BFBS edition (1908) | Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1976) | Stone edition of Tanach (1996) |

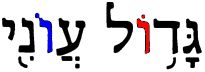

Figure 1: Holam Male (marked in red) and Vav

Haluma (marked in blue)

distinguished in ancient

and modern editions of the Hebrew Bible - these words are from Genesis

4:13.

(If the colours are not visible: In each image, the third base

character from the right, with the

dot above its right side or its centre, is Holam Male; the third base

character from the left, with the dot above

its left side, is Vav Haluma.)

|

|

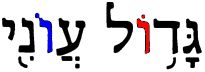

Figure 2: Holam Male (left, twice, red, from

p.529) and Vav Haluma

(right, blue, from p.528) contrasted

in Keil & Delitzsch Commentary

on the Old Testament,

vol.1, reprint by Hendrickson, 1996 (Hebrew words quoted in English

text).

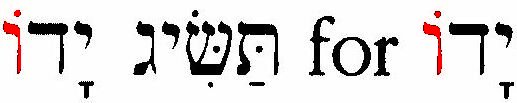

Figure 3: Holam Male (right Hebrew word, red) and Vav

Haluma (left word, blue)

contrasted

in Langenscheidt's Pocket Hebrew

Dictionary, p.243.

|

|

|

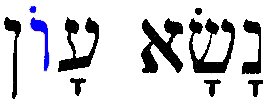

Figure 4: Comparison of positions of HOLAM

after HE and with VAV in Biblia

Hebraica Stuttgartensia. Left: regular Holam Male, from Joshua 10:3.

Centre: HOLAM dot

not shifted on to consonantal VAV, as this is not Holam Male, from Ezekiel 7:26.

Right: HOLAM dot shifted to Holam Male position on a

consonantal VAV in the divine name, although this is

not Holam Male, from Exodus

13:15.

The Unicode Hebrew block is based on the Israeli national standard

SI 1311. This standard was originally designed for unpointed modern

Hebrew texts, although later extended to cover points (SI 1311.1) and

accents (SI 1311.2) (see http://qsm.co.il/Hebrew/stdisr.htm

for further details), but was not designed for full support of biblical

Hebrew. As a result there are some minor inadequacies in the Unicode

support for biblical Hebrew.

The most significant of these inadequacies, because it is the only

one which affects the vowel points rather than only the accents, is

that there is no support for the distinction between Holam Male and Vav Haluma. There is a single VAV

character and a single HOLAM character, and only one

way of combining these two, the sequence <VAV, HOLAM>,

which is apparently intended to be used for both Holam Male

and Vav Haluma. There is

thus no defined way of distinctively encoding either Holam Male or Vav Haluma.

The alphabetic presentation form U+FB4B HEBREW LETTER VAV WITH HOLAM cannot be used for Holam Male distinct from Vav Haluma, because it is canonically equivalent to the sequence <VAV, HOLAM>, i.e. it has a canonical decomposition (which cannot be changed) to 05D5 05B9. It is included in Unicode for compatibility purposes.

Because there is a real need to

distinguish between Holam Male

and Vav Haluma, but there is

no standard way of doing so, various ad hoc solutions have been used by

text providers and by font developers. The Hebrew Bible text from

Mechon Mamre (at Genesis 4:13, http://www.mechon-mamre.org/c/ct/c0104.htm#13)

uses <VAV, HOLAM> for Holam Male and <VAV,

ZWJ, HOLAM> for Vav Haluma. The "alpha release"

text at http://whi.wts.edu/WHI/Members/klowery/eL/leningradCodex-alpha.zip

and the text at http://users.ntplx.net/~kimball/Tanach/Genesis.xml

use (again at Genesis 4:13) <HOLAM, VAV>

(actually <HOLAM, accent, VAV>

according to canonical ordering) for Holam

Male and <VAV, HOLAM> for Vav Haluma, and this is also the

encoding recommended in the documentation for the fonts SBL Hebrew and

Ezra SIL. There is however a larger body of existing data, including

pointed modern Hebrew and some biblical texts (e.g. the one at http://www.anastesontai.com/b-cantilee/en-cant.asp?A=1&listeB=4),

in which Holam Male and Vav Haluma are not distinguished

but are both encoded as <VAV, HOLAM>.

To avoid this inconsistency and potential confusion, it is proposed

here that

the UTC should specify distinctive encodings for Holam Male and Vav Haluma, for use when these two

need

to be distinguished. Various options for these distinctive encodings

are

discussed below. It is noted that

although Option B2 below can technically be chosen without UTC

involvement, because it involves only a spelling rule, the other

options do require UTC approval as they involve either sequences with ZWJ

or ZWNJ or a new character.

There are various possible distinctive encodings for Holam Male and Vav Haluma. (Some of these are

already summarised in http://qaya.org/academic/hebrew/Issues-Hebrew-Unicode.html,

section 2.3 and appendix B.1.) All of these options are based on the

assumption that <VAV, HOLAM> will

continue to be a valid encoding for both Holam Male and Vav Haluma when there is no need to

distinguish them, as commonly in modern Hebrew text. It is desirable

that rendering and other processes will fall back to treating these two

as identical when no deliberate distinction is being made, e.g. when a

font is applied which does not have special features to support Holam Male and Vav Haluma distinctively, or for

collation unless

a tailoring is applied to distinguish the two. (It is noted that

because in the current Default Unicode Collation Element Table (DUCET) VAV

and HOLAM have weights at different levels, for

practical purposes <VAV, HOLAM>

and <HOLAM, VAV> collate together,

and ZWJ and ZWNJ are ignored, except at

the binary level. Therefore with all of these options Holam Male and Vav Haluma collate together except

at the binary level.)

In most of the options (but not in Options A2, A3, C3 and C4) the

recommended encoding for Vav Haluma

is simply <VAV,

HOLAM>.

Although Vav Haluma is less

common than Holam Male, this

corresponds to the regular use of HOLAM with other

Hebrew consonants; this is the reason for using the specially marked

encoding for more common case.

Following this list of options and a summary of their advantages and

disadvantages, the preferred encoding

and proposal to the UTC is given.

These options are called "graphical structure solutions" because

they represent the dot in Holam Male

according to its graphical association with the VAV.

This option effectively takes Holam

Male as a variant of <VAV,

HOLAM> with "a more connected

rendering" (to quote from The

Unicode Standard, version 4.0, section 15.3, p.390). This more

connected rendering is indicated by inserting U+200D ZERO

WIDTH JOINER (ZWJ) between VAV and HOLAM.

This option was earlier rejected because ZWJ and ZWNJ

were not permitted between a base character and a combining character.

But this restriction was partially relaxed at the February 2004 UTC

meeting. This option depends on a small further relaxation of this

restriction.

This encoding has the advantage that the fallback behaviour should be automatically as required. One disadvantage is that as a layout control character ZWJ is intended for making rendering distinctions which have no other semantic significance. However, there are already several defined uses of ZWJ and ZWNJ with Arabic and Indic scripts which do have other semantic significance. There are similar objections to any possible variant of this option using Variation Selectors.

There are no known existing implementations of this option. However,

it would be simple to support in fonts.

This option, as well as Options B1 and B2, implies that undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM will be rendered like Vav Haluma, not like Holam Male. In fact it seems that many typesetters who do not generally distinguish Vav Haluma from Holam Male render the HOLAM dot above VAV further to the right than the HOLAM dot indicating Holam Haser when used with other letters, for example with YOD whose upper part is usually the same as that of VAV. This suggests that if in a particular text these typesetters did need to distinguish Vav Haluma from Holam Male, the glyph they would use for Vav Haluma would not be the one which they used for undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM.

Another disadvantage of this option is that each Holam Male consists of three

Unicode characters, including ZWJ which takes three

bytes in UTF-8. This increases the size of the encoded Hebrew Bible,

relative to Options A2 and B1 (in which Holam Male consists of two

characters), by 34,000 characters and more than 100,000

UTF-8 bytes, i.e. around 2% of its total length.

This option differs from

Option A1 in that the

simple

sequence <VAV, HOLAM> is used for Holam Male, rather than for Vav Haluma. The proposed sequence

for Vav Haluma uses U+200C

ZERO WIDTH

NON-JOINER (ZWNJ), because Vav

Haluma is a less

connected rendering than Holam Male.

This option has the advantage

that the longer and more complex sequence is used for the less common Vav Haluma, but the disadvantage

that consonantal VAV is treated differently from all

other Hebrew consonants in how it combines with Holam Haser. The fallback behaviour

of this option should be as required.

This sequence was rejected earlier for the same theoretical

reasons as Option A1, but for the same reasons it can now be

considered acceptable.

This option implies that undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM will be rendered like Holam Male, not like Vav Haluma. It may therefore represent more closely than Options A1, B1 or B2 the practice of typesetters who do not normally distinguish Vav Haluma from Holam Male but may have to for certain special texts.

The encoding already used by Mechon Mamre is similar to this option except that ZWNJ is replaced by ZWJ. This encoding is apparently supported by existing some fonts and rendering engines, but this support may be largely accidental, because the ZWJ unintentionally breaks a rule to position HOLAM centrally over VAV. The long term encoding of text should not be determined in this way by unintended features of current implementations.This option differs from Options A1 and A2 in that explicit

sequences with ZWJ or ZWNJ are used to distinguish both Holam Male and Vav Haluma from the

undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM. This

allows typesetters to make a three-way distinction, distinguishing

undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM both

from Holam Male and from Vav Haluma. It is uncertain whether

this is ever necessary. Again, the fallback behaviour of this option

should be as required. Otherwise, this option seems to have the

disadvantages of both Options A1 and A2.

These options are called "logical structure solutions" because they

represent the dot in Holam Male

according to its logical association with the preceding base character.

In all of these solutions Vav Haluma

and undifferentiated VAV with HOLAM are

represented as <VAV, HOLAM>.

In this option Holam Male

is distinguished from Vav Haluma

in that HOLAM is encoded before VAV.

This appears to be a breach of the Unicode rule that combining

characters must follow their associated base characters. But it is not

really a breach of the rule, because the HOLAM

in Holam Male can be

understood as

logically associated with the preceding base character, for which it is

the associated vowel, and the VAV is a separate silent

letter. On this analysis Holam Male

is

analogous to Hiriq Male, i.e.

HIRIQ

followed by silent YOD, in which the HIRIQ

is written below the preceding base character; also to the sequence of HOLAM

with silent ALEF, which is encoded unambiguously in

this order although the HOLAM is often rendered above

the top right side of the ALEF.

With this encoding, the HOLAM is for Unicode purposes linked with the preceding base character in a combining character sequence. The HOLAM will often become separated from the VAV by an accent character, because within a combining character sequence accents are sorted after vowel points in canonical ordering and also in the specific orderings recommended for certain fonts.

The fallback behaviour of this encoding, with a font which has not

been set up to work with it, is not ideal but still legible: the Holam Male will be broken up, with

the HOLAM being rendered above the left side of the

preceding base character.

Some existing texts use this encoding, and it is supported in

OpenType fonts

such as SBL Hebrew and Ezra SIL, with Microsoft Windows only. However,

this implementation proved to be very complex, and may be beyond the

capabilities of other rendering systems.

The complicating factor is the rule that Holam Male is not formed, and so HOLAM

is not shifted on to a following VAV, if the VAV

is consonantal and followed by a vowel, except in the divine

name. This rule, which is illustrated in Figure 4 above, is complex and

not entirely conditioned by the immediate glyph or character

environment. In most cases it is possible in principle, although rather

complex, to determine within the font which VAVs are

silent and so may form Holam Male;

the rule is that if VAV is followed by any Hebrew point

or accent it is not silent. But there are two cases where this is not

possible. Firstly, a VAV followed by Holam Male or by Vav Shruqa (i.e. VAV

with DAGESH acting as a vowel; but this combination may

also be consonantal) is consonantal and so cannot form Holam Male, but any attempt to

distinguish these cases within a font is potentially recursive and well

beyond the capabilities of existing rendering systems. (This situation

does not occur in the Hebrew Bible, but it can do in modern Hebrew.)

Secondly, in at least one major edition of the Hebrew Bible, when the

divine name is written with HOLAM (which is in a small

minority of cases) the HOLAM dot is positioned over the

VAV as in Holam Male

although the VAV is consonantal and carries another

vowel point and usually an accent; this case can be distinguished from

a similar word in which the HOLAM is not positioned as

in Holam Male only from the

remote context, in a way which is clearly outside the scope of any

rendering system - see the centre and right hand images in Figure 4.

Since it is beyond the reasonable scope of a rendering system to determine in every case whether Holam Male should be formed or not, there is a need to define more specific encodings at least for certain marginal cases. Thus, for example, formation of Holam Male could be inhibited by the sequence <ZWJ, HOLAM, VAV>, which would indicate Holam Haser followed by consonantal VAV; but this formation could be promoted by the sequence <ZWNJ, HOLAM, VAV>, which would indicate the rendering of the divine name as in the right hand image in Figure 4. The implication of this is that Option B1 does not in fact have the simplicity which it appears to have at first sight.

This option differs from Option B1 in that HOLAM is

preceded by ZWNJ to separate it from the preceding

combining character sequence. Again, this is a sequence which was

rejected earlier for the same theoretical

reasons as Option A1, but for the same reasons it can now be

considered acceptable. The HOLAM is technically and

logically combined with the preceding base character as in Option B1,

but the intervening ZWNJ can be understood as

indicating that it should not be combined graphically.

With this proposal, any accents and other combining characters which

are graphically as well as logically associated with the preceding base

character should be encoded before the ZWNJ. The ZWNJ,

which is in combining class 0, inhibits canonical reordering, and so

these other combining characters will never be moved to between HOLAM

and VAV. The ZWNJ also explicitly

signals that the HOLAM is to be shifted to form Holam Male or as in the divine

name, and so distinguishes

this from the cases in which the HOLAM dot remains on

the

preceding base character before consonantal VAV. This

implies that it is significantly simpler to

implement Option B2 than Option B1.

This option has the same disadvantage as Options A1 and A3 that the

length of a text is significantly increased. Its fallback behaviour

should be the same as that of Option B1.

The common factor with these options is that a new Unicode character

is proposed. They have the common disadvantage that they have very poor

fallback behaviour when used with fonts which do not support the new

character. Some experts have commented that any of these solutions have

the effect of making existing uses of HOLAM illegal. In

fact the definitions could be carefully written so that existing uses

are not made illegal but only deprecated. Nevertheless, this effect on

existing texts is a significant argument against any of these new

character solutions.

In some ways the simplest option of all is to define a new Unicode

character HEBREW LETTER HOLAM MALE, which might have a

compatibility decomposition to <VAV, HOLAM>.

This would certainly be simple to implement, and would reduce the size

of the encoded text. But it would have no suitable fallback behaviour

with fonts which do not support this new character. This solution also

loses the essential identity of the HOLAM and the VAV

in Holam Male with HOLAM

and VAV in other contexts.

This is the first of three options based on defining a new second combining character for a variant of HOLAM. Thus one of the variants of HOLAM can be used for the dot in Holam Male, and the other variant can be used in Vav Haluma. These options are reasonably simple to implement. They have the small advantage over Option C1 that the identity of VAV, though not of HOLAM, is preserved.

In this option, the new combining character is HEBREW POINT RIGHT HOLAM, and is to be used only in combination with VAV to form Holam Male. The existing HOLAM character is to be used only for Holam Haser, when combined with any Hebrew consonant. The fallback behaviour is good for Holam Haser but not for Holam Male.

In this option, the new combining character is HEBREW POINT HOLAM HASER, and is to be used for Holam Haser when combined with any Hebrew consonant. The existing HOLAM character is to be used only in combination with VAV to form Holam Male. The fallback behaviour is good for Holam Male but not for Holam Haser; this may be preferable to the fallback behaviour of Option C2 because Holam Male is commoner than Holam Haser in modern Hebrew.

In this option, the new combining character is HEBREW

POINT LEFT HOLAM, and is to be used only in combination with VAV

to form Vav Haluma. The

existing HOLAM character is to be used in combination

with VAV

to form Holam Male, and for Holam Haser in combination with

consonants other than VAV. The fallback behaviour is

good except for the relatively rare Vav

Haluma, i.e. Holam Haser

with VAV. But this option introduces an entirely

illogical

distinction between Holam Haser

with VAV and Holam

Haser with other

consonants, which is justified neither by character semantics nor by

typography.

| Option | Summary |

Fallback Behaviour |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

| A1 |

Holam Male = <VAV, ZWJ, HOLAM> |

Excellent |

Best fit to the graphical

structure of Hebrew script; best

fallback behaviour |

ZWJ used

within combining sequence and with

semantic significance; long sequence for a common character |

| A2 |

Vav Haluma = <VAV, ZWNJ, HOLAM> |

Excellent |

Best fit to the graphical

structure of Hebrew script; best fallback behaviour; long sequence only

for a rare

combination |

ZWNJ used within combining sequence and with semantic significance; arbitrary use of different sequence for Holam Haser in the context of VAV |

| A3 |

Holam Male = <VAV, ZWJ, HOLAM> and Vav Haluma = <VAV, ZWNJ, HOLAM> | Excellent |

Best fit to the graphical

structure of Hebrew script; best

fallback behaviour; support for possible three-way HOLAM

positioning distinction |

ZWJ and ZWNJ used within combining sequence and with semantic significance; long sequence for a common character; arbitrary use of different sequence for Holam Haser in the context of VAV |

| B1 |

Holam Male = <HOLAM, VAV> |

Legible |

Best fit to the logical

structure of Hebrew script; existing

implementations and texts |

Most complex implementation;

difficulties with unusual

combinations e.g. the divine name |

| B2 |

Holam Male = <ZWNJ, HOLAM, VAV> |

Legible |

Best fit to the logical

structure of Hebrew script; implementation much easier than Option B1 |

ZWNJ used within combining sequence, but with only graphical significance; long sequence for a common character |

| C1 |

New

character HOLAM MALE |

Holam Male illegible |

Simplest implementation |

Bad fallback behaviour; unity

of VAV and HOLAM

lost |

| C2 |

New character RIGHT HOLAM | Holam Male illegible |

Bad fallback behaviour; unity

of HOLAM lost |

|

| C3 |

New character HOLAM HASER | Holam Haser illegible |

Bad fallback behaviour; unity

of HOLAM lost |

|

| C4 |

New character LEFT HOLAM | Vav Haluma illegible |

Few characters affected by

bad fallback behaviour |

Unity of HOLAM

and of Holam Haser lost;

arbitrary use of

different character for Holam Haser

in the context of VAV |

Assuming that the objections to sequences with ZWJ

or ZWNJ between base characters and combining

characters no longer apply, all of the options above can be considered.

Theoretically the neatest of these is Option A1. It is also easy to

implement in practice. The only significant objection to it is the

2% increase in the length of the text. But that objection should not be

given too much weight, given that storage is cheap and compression can

be used for transmission.

Options A2, A3 and B2 are considered to be acceptable alternatives

to Option A1. Option B1 is rejected because its apparent simplicity

masks serious complications. And all of the new character solutions are

rejected because of their incompatibility with existing fonts and

implementations.

But the preferred option is Option A1. So this proposal is

that Holam Male should be

encoded, when it needs to be distinguished from Vav Haluma, as

the sequence <VAV,

ZWJ, HOLAM>; and that the sequence

<VAV, HOLAM> should be used always

for Vav Haluma, and for Holam Male when not distinguished

from Vav Haluma. Furthermore,

because

this option involves a sequence with ZWJ, and also

because it is desirable that the encoding be clearly standardised to

avoid confusion, it is proposed that the UTC specify this as the

correct encoding for Holam Male

when distinguished from Vav Haluma,

and that this

specification should be added to Section 8.1 of The Unicode Standard, perhaps after

the existing subsection Shin and Sin.